The blog

Guernsey and Leros

View from the 10th century castle on Leros, Greece.

There are only a few books that are composed completely of letters, and one of them happens to be among my favorites (mind you this is a long list): The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. Guernsey is a small British island that is actually very close to France, so it was occupied by German soldiers during WWII. Much like the occupation of France and the rest of the European countries during the war, the citizens of Guernsey suffered all kinds of indignities and atrocities under the German soldiers’ occupation, ranging from having their homes overtaken to billet soldiers and officers, to their resources depleted to support the German war machine, to their food supplies taken to feed the German army while they starved, to their lives strictly monitored and controlled, and most brutally, to their women raped. Not unlike Guernsey, my family is from a small island that was also occupied by the German army during WWII, but this island and their experience is lesser known. After enduring 52 straight days of bombing raids and five days of a vicious ground war to take Leros, Greece, the German army first ravaged and then secured its presence on Leros for the last two years of WWII. And they behaved toward the Lerians as they did toward the other places they occupied – abominably.

View of Agia Marina from the Castle

My dad told me of a legend where my great grandparents were just two of their victims on Leros. Because my great grandfather, Papa Markos, was a priest who oversaw all of the schools on the island and he orchestrated the survival of the civilian population during the bombings by making sure everyone knew to seek shelter in the caves, he was dangerous to let live. So they didn’t. Rather, they drug him and my great grandmother behind their tanks through the streets until they were barely alive and then they buried them in one of those caves to die of their injuries – as an example.

This is an example of the caves the people spent almost two months living inside while the German army bombed the island. They are dark, and smell strongly of goat.

This took place in the middle of November, 1943, just after they took control of the island. It is now September, 2024, and I was there to learn all I could about him, his life, and his story. To this end, I was visiting the Merika Tunnel War Time Museum in Lakki, Leros. It is a collection of Italian, British, and German war artifacts, photos, and film of WWII and The Battle of Leros built into a series of tunnels, much like the tunnels the Italian and British soldiers used as headquarters during the battle and the civilians used to take shelter during the 52 days of bombing. And, much like the tunnel where my great grandparents supposedly died of their injuries.

As I waited behind an older British couple at the museum while they purchased their tickets for 3 euro each, the gentleman asked the woman tending the desk if she had heard of Guernsey. She had not. He went on to explain quite bitterly that his wife is from Guernsey, a small island that was also occupied by the German army and that they suffered greatly. His wife started to chime in with some gruesome details about the Guernsey occupation and Germans in general when the woman saw me behind them and politely tried to move them along by saying, “My family wasn’t here during the war.”

He continued for a few moments and then ended with a sarcastic and self-righteous, “gotta love those Germans.” I felt my morning coffee and avocado toast curdle in my stomach. I have read The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. I have some idea of what those innocent people suffered while occupied. But for a British man to scoff at “those Germans,” as if Great Britain had never inflicted suffering on an innocent people, had never imposed their will on another country and ravaged their resources, had never stood by well-fed themselves as oppressors while the people they occupied starved, to say the least. It more than annoyed me. It sounded as audacious to me as an American self-righteously complaining to an African about human trafficking or the horrors of slavery, or to a Native American about genocide. They may not have been your hands inflicting the direct harm, but a disposition of humility, an understanding of history, and a sense of shared humanity would caution one against blindly ignoring what your own people have done.

I don’t mean to dismiss or demean the suffering that was inflicted on the people on Guernsey or Leros or all across the whole of Europe, Northern Africa, throughout the south Pacific, and for sure in the camps where the German army tried to extinguish the Jewish population during WWII. I only think it is important that while considering the blood on others’ hands, collective or individual, we also recognize the blood on our own, collective and individual. One does not have to inflict the ravages of war to understand the harm we have inflicted on others.

There has only ever been one set of innocent hands in this world. And those hands were bloodied and later extended to a beloved doubter for the nail scars to be touched with his own. It's a tension for sure, moving about in the world as a person seeking to be mindful of the blood on my own hands and the doubts that cloud my own faith, and as someone who asks for and freely receives forgiveness from the one whose innocent hands were bloodied to extend it.

Inside the courtyard of the castle on the hill overlooking Agia Marina. This castle and the church inside it from the 10th century was unharmed during the 52 days of bombing.

Drowning Within Arms Reach of a Boat, while wearing an inflatable vest - almost

I am someone who can get overcome by her emotions – particularly when I’m excited. If I’m super jazzed or amazed, lay reason aside and the experience takes over. Recently, my husband I were on the Greek island, Leros where my grandparents immigrated from back in the 1920s. It’s also the site of a pivotal WWII battle and I was there to learn more about the role my great grandfather played in saving the Greek civilian population - or at least that’s what my father had always told me. Part of the research involved scuba diving to four sites in the cerulean blue waters that surround the island to see downed British and German planes and a German landing craft from the epic battle. Are we certified divers, not at all; however, we have ventured under the water before, but it’s been many years.

Our young guide, Tsassis, was busy gathering our gear in the salty dive shop, sizing the booties and masks, as he asked about our diving experience. We told him we had done this before, me five years ago and Vince about 15 years ago. On those occasions, we donned the equipment and practiced each of the critical safety skills in the water. But, Tsassis decided we had enough prior experience and just ran down how to unplug one’s ears, equalize the pressure in one’s mask, inflate and deflate the vest to sink to the depths and rise to the surface, and reviewed the hand signals of thumbs down to go deeper, thumbs up to ascend, the ok sign to indicate all is well, and a waving back and forth of the hand in a “so-so” sign to indicate all was not well. All this was covered as he puttered about loading bins and throwing instructions over his shoulder like they were snacks for an afternoon walk. I fully expected we would then dress in the soggy wetsuit, mask, flippers, tank, and practice. But, he said, “Ok, please gather your bin and let’s go.” As in, the boat’s leaving.

This is Tsassis, our dive captain!

A kind Greek man named Gustav was also joining us on this dive, but he was a certified, very experienced diver. In fact, so experienced that our first stop was at a site where only he and Tsassis were diving in a cave that was far beyond my and Vince’s abilities and comfort levels, but it also put another 60 minutes between me and the instructions we so hastily heard: 30 minutes for their dive and another 30 for the nitrogen to leave their blood so they could dive again with us at the German plane on the bottom of the Aegean sea.

Sitting on the back of the boat, wet suit fully zipped up over my chin with all of my white hair tucked neatly into the hood so as not to break the seal on my tightly fitting mask, flippers strapped on my feet making it impossible to take a forward step, Tsassis tightened a belt around my waist with six five pound weights strung along it like Christmas lights and hoisted the heavy vest holding the oxygen tank that would sustain my life while under the water onto my back. He tucked hoses and straps here and there, saying nothing as he worked just inches from my nervous expression. Checking one last time that everything was in its correct place, he tucked the few strands of my hair that the wind had pulled to freedom back inside the moist hood, snagging them painfully as he worked. When he was satisfied, he inflated my vest with the red button by my right hand, put the regulator in my mouth, mimed for me to cover it with my hand and pointed to the crystalline water where Gustav and Vince bobbed behind the boat. I was sure he could hear my heart pounding at the thrill of what was to come.

I didn’t notice Tsassis adjusting the air in my vest as we descended. I was concentrating on my breathing. I am well acquainted with breath work to keep my heart rate down, but it is a deep inhale through my nose and a long exhale through my mouth, so I had to really concentrate to breath slowly in and out through my mouth and make myself relax and know I was just fine breathing under water, more so the deeper and deeper we went. I continually plugged my nose and released the pressure in my ears, feeling and hearing a small squealing noise most times. I was so proud of myself for how well I was doing. It wasn’t long, maybe 10 or 15 fee down, when my face started to feel like a giant was standing on it. The pressure from my mask was intense, and I was not happy about it, but I was determined to be tough and not be the cause for everyone to have to return to the surface because my mask was ill-fitting. So, down we went. Tsassis left to go retrieve Vince, who had gone too far off on his own. Classic Vince. When he returned, we were now about 30 feet deep, I had released the pressure in my ears many times, but the pressure on my face was becoming intolerable. It was as if a ratchet was being tightened around my head with every movement. Tsassis came back to me and questioned with the ok sign. I gave him the “something is amiss “so-so” hand signal back. He responded quickly by swimming right in front of me and noticed the distress on my face.

Action shot of me clearing the pressure in my ears.

Directly in front of me, he put his palm on the top of his mask, tilting it upward. I thought to myself, “duh, there’s no way I’m doing that. The last thing I need to deal with on top of this pain is having water in my mask too. I won’t be able to see.” So I shook my head no. He nodded his head yes and demonstrated again in more exaggerated fashion the mask tilting he wanted me to do. At this point, I just wanted him to leave me alone, so I just lied to him and gave him the ok sign, making him think I had in fact equalized the pressure in my mask. We continued downward, the pressure on my face moving from a giant standing on it to a car resting on it until it got to a point where I stopped moving and rigormortis set into my body. Tsassis was once again off herding Vince back to a safe distance when he noticed my increased distress. This time he moved so his face was within an inch of mine and blew out through his own nose, forcing air out of his mask, two or three times. And it finally dawned on me that I needed to equalize the pressure in my mask to relieve the pain I was feeling. I mimicked him and the relief I felt on my face was like draining the blood from a finger swollen from being slammed in a door. I gave him the ok sign and this time I wasn’t lying to the very person there to keep me alive.

Me, experiencing some distress. Notice how stiff I am.

The German plane settled on the sea floor about 50 feet deep. The engine was in the War Tunnel museum, the canvas wings and fuselage were long deteriorated by the salt water and its inhabitants, but the steel frame and cockpit with its instrument panel, yoke, and tiller covered in green that could be easily wiped to see Bosch printed on the side of the engine compartment and instructions on the panel printed in German amazed me. I could put my fingers through the bullet holes that pierced the metal surrounding the cockpit, making it soberingly clear this was a grave site, not just a war relic. Concentrating, I was able to keep my breath steady, but my deep interest in history, WWII history, and this particular island’s history that is spun together with my family’s history like thread into one ball had my emotions roiling.

The engine from the German bomber that now resides in The War Tunnel Museum.

While the guys were serenely floating along, hands gently clasped together in front of them as they took in the plane and brightly colored fish, I was struggling to keep my body stable. My tank kept getting off center on my back, barrel rolling me along the bottom of the sea. When Tsassis finally gave us the thumbs up signal indicating it was time to ascend to the boat, I was relieved. The constant vigilance it took to keep the pressure in my ears cleared, the pressure in my mask equalized so my face didn’t hurt, my failed attempts to keep my body floating calmly in the water, and managing all my thoughts and questions about the plane and pilots, my emotional and mental resources were tapped. Tsassis lead the way, Vince and Gustav followed along, and I started swimming and kicking my flipper equipped feet as hard as I could to keep up with them. But the weight of my belt and tank were strong contenders against my strength. It wasn’t but three or four strokes of my arms before the nausea welled up in my stomach like a geyser threatening release. It was my strongest urge to be on the surface as fast as possible, but I knew you had to ascend slowly and release the pressure in your ears as you went, plus, I could only swim so fast given the weight I was fighting. Swallowing, swimming, and breathing consumed my concentration.

When I finally saw the bright light of the sun, I kicked my hardest and pulled just enough water with my arms to get only my mouth of the water and vomited out a burst of avocado toast and took in a mouth full of sea water before my tank and weight belt pulled me back under. I was aware that I was within arm’s length of the side of the boat, so I kicked my hardest and pulled again with my arms, and as my mouth tasted the open oxygen of the surface, I reached for the boat. But when I stopped swimming, the weight of the tank and belt were too much for just one arm and my kicking so in the few seconds I surfaced, I vomited more avocado toast, took in more sea water, and barely heard Gustav shouting, “sick, sick, sick,” and I was pulled back under. The thought that I was drowning lingered near my consciousness, but I was still fighting my way back to the surface.

Kicking for all I was worth and pulling with both arms in my best effort to reach the boat for the third time, I propelled myself directly into Tsassis who had come to my aid. I noticed I was no longer struggling to reach the surface, but was easily bobbing on the top of the water, and vomited up two more gushers of avocado toast mixed with sea water. With my arms now free of their responsibility to get me to the boat, I quickly pushed the slimy mess away from us, apologizing for making him swim in my puke and afraid of the fish that were sure to swarm us for the fresh chum. It was then I noticed Tsassis was pushing on the small gray button at my right hand to inflate my vest with air, making me incredibly buoyant so I no longer had to struggle to stay on the surface. He guided me to the back of the boat while removing my flippers so I could easily climb the ladder. As I sat beside Vince, who was up to this point unaware of any of my distress and calamity, I took off my mask to reveal two swollen and blackening eyes, the white of the right one blinking red like a tail light from broken vessels – the result of the first 10 minutes when I had not equalized the pressure in my mask, refused help, and lied to the expert right in front of me there to give it.

Looking at Vince’s concerned and confused face, I shrugged out, “I forgot how to solve my problems.” Me being overcome by my excitement and amazement is something he is familiar with, but the stakes being my very life have never been on the table. He put his arm around me and pulled me into his shoulder.

Later that day, as I sat on the beach by our rented house, I was reflecting on this experience and the Lord spoke to me about how I sometimes forget how to solve my problems in my faith walk – how I can be so overcome by the pain pressing in on me that I forget how to release it, to trust him, to believe who he says he is, to know I am loved, sometimes lie to those there to help me, get tossed around – even barrel rolled – by the waves coming at me and kick and pull with all my own strength and nearly drown within arm’s reach of the boat while wearing an inflatable vest.

You see the story I traveled all the way round the world to research was one my dad had told me many, many times about his grandfather, my great-grandfather. His name was Papa Markos Papageorgiou; he was a priest on this tiny Greek island. According to the story my dad told me, he died a violent death at the hands of the German army after saving the entire Greek civilian population of the island. The British army wanted this island for strategic military reasons and a few personal reasons for Churchill. The German army wanted it for different strategic military reasons. Between September, 1943 and November 16, 1943, a vicious battle for this tiny place ensued. The German army bombed the 9 mile long and 6 mile wide island for 52 straight days before invading to fight a non-stop 5 day ground war, which preceded the last German victory that gained them any new territory in all of WWII, and conversely, the last British defeat losing them any territory. As my dad told it, Papa Markos ushered the civilian population into caves and tunnels for the entire assault. When it was over, the victorious German soldiers drug him and Maria, my great grandmother, through the streets behind their jeeps until they were barely alive and then buried them in one of those caves to die of their injuries.

On my second to last day on the island, I met with a local historian named Christina who also worked for an architect to see if she knew anything of Papa Markos and this remarkable, although tragic story. For, in my three weeks on the island, I had been to the War Tunnel Museum, the Town Hall where the island’s birth and death records are kept, the church administration building, the library for several days, and talked to dozens of people, many who who could tell me a lot about and provide books with the story of Papa Markos as a priest and superintendent of schools on the island in the late 19th and first several decades of the 20th centuries. But no one had ever heard this story. Christina said she and the architect she works for frequently partner with some civil engineers on the island with the last name Papageorgiou and before I could say a word, she was on the phone speaking Greek. She then handed me the phone to talk to who I could only assume was someone with the last name Papageorgiou.

I began, “Hello, my name is Traci and I’m here from Seattle, Washington in the United States looking for information about my great grandfather. His name was Papa Markos Papageorgiou.” There was a brief pause before I heard back in a tentatively amazed voice ,

“Oh, I have relatives in Seattle and my great grandfather’s name was Papa Markos Papageorgiou. I think we are second cousins. My father and I are working on another island today but we will be back tonight. Will you please come to our office tonight at 8:00?”

I agreed and he hung up the phone.

That night at their civil engineering office, after some warm hellos and learning of who is who and who is where in the family tree, all translated from the younger Mihailis to his father Dimitri, I eagerly asked about the infamous story from the WWII battle my dad told me so many times, the story I came all this way and spent so much time and energy to find. Mihailis’ lips pursed slightly and his eyebrows drew together as in concentration as I described the heroic actions and violent death. He looked to his father and began to, I assume recount my tale in Greek. I watched Dimitri’s face as he listened. This was his grandfather after all. His father would have lived through it. He would know. As Mihailis spoke, Dimitri’s mouth drew into a tight line and the corners drew down along with his eyes as he ever so slightly shook his head while responding to his son. Slowly, Mihailis turned back to me and gently, but clearly said, “That’s just not true. It just didn’t happen. They died peacefully at home - of old age - before WWII even started.”

I was only a little surprised. For I had come to deeply question the story as I learned so very much about Papa Markos in my time on the island, but could not find this story. My first thought was complete and utter relief that they did not die a violent death. My second thought was what happened to his remaining four children who had not moved to the United States? My third thought was a sense of curiosity as to why my dad would have told me such a story. I knew it was not the story he was told for his sister’s son had never heard of it. And long down the line was an old sense of not even anger that he’d lied to me but something softer than anger. Not the old feeling of being made to look like a fool for believing him. I did register those feelings, but they were watermarks to the full color prints they used to be when I learned he, my mom, and my family had been lying to me about the identity of who my father really is until I was an adult. And the Lord brought back to my mind, “don’t forget how to solve this problem and drown within arm’s length of the boat while wearing an inflatable vest with this.”

I leaned into the knowledge of who I am as a loved child of God. I remembered that I had been praying for months prior to my trip that I would find Papa Markos’ story. As I found everything but the ending, I kept praying, please let me find out what happened to him. And I recalled what Paul taught in Philippians about presenting your requests with thanksgiving and then the peace of God will guard your heart and mind. I was thankful for this answer, even though it was not what I expected, even though it shed light on a lie, it was an answer to my prayer, and God’s peace guarded my heart and my mind. In those things, I dwelled and in those things I found rest, as Psalm 91 starts. It’s very hard to rest, take shelter - refuge even, in unfamiliar surroundings. The best rest is found where you dwell. Remembering that was worth every second of the struggle.

Getting Beans Back

At this point in my life, I have three grand-dogs. One is a French Bulldog named Beans and the other two are Corgis named Hanzo and Fern, who are siblings.

Aside from the obvious difference between these dogs, an important thing to know about them is if Hanzo or Fern squirt past you at the front door, they will wag their adorable corgi butts a short ways and come right back when called. Beans, on the other hand, will dart faster than you could ever think his stout frame could possible move and never look back, not even for cheese. Your only chance of getting him back is the fact that he can barely breath when at complete rest, so he’s no endurance athlete. He just loves to be chased. You also have the fact that his constant struggle for oxygen must keep his brain deprived of what it needs to be clever enough to outwit anyone who has two digits to their age. Because he is dearly-loved and cost the equivalent of a European vacation (when you include the not one, but two surgeries he’s needed to make it so he can eat without vomiting and breath to the extent that he can), his parents and all who are charged with being responsible for him take the greatest care to never let him escape. But, he finds a way on occasion, and when he does, oh the terror his parents feel, the panic that ensues, the strategies to re-capture his devious little self, the enlisting of help from any and all on hand, and the scorn-filled relief they feel when he is corned and caught. I’ve seen his mamma dive and catch him by just one back foot and hold tight while his dad rushes in to scoop him up, panting and gasping for all he’s worth (Beans, not his dad).

You might think with his lack of endurance and less than stellar intelligence, it might not be that difficult to catch him. You’d be wrong. He makes up for his clear deficits with blind enthusiasm for the chase. His huge brown eyes somehow double in size as he assumes his best downward dog, baiting you to reach for him. He’s a master of the lean left, juke right, and then go left. Or, maybe he’ll just go left without the juke. One never knows. How do I know this, you may be wondering? I dog sit for Beans quite frequently when his parents go out of town. And they dog sit for my dog, Chewie frequently when we go out of town. It works great, until we want to go out of town together as a whole family. On one such occasion, I asked one of my co-workers and his wife, Peter and Christy, who are good friends, to come to our home for a long weekend and watch both dogs. They graciously agreed to Rover for us. Because they’ve been to our house plenty, they’re very familiar with Chewie, who never tries to escape, ever. Nothing to worry about there. She’s an old, sweet, very low maintenance dog. I warned them to not be fooled by the vacant look on Beans’ face and the slow way he meanders up to the open front door. He cannot get out, or God help you in getting him back. And they were so vigilant. They never once let their guard down at the front door. I also warned them about the gate on the side of the house because there is access from the backyard, so it has to be kept latched. So, every time they came home, they double checked it was latched before they came in to let the dogs out into the backyard. The trouble is, this is a shared gate with my unsuspecting neighbor, Mary and her well-behaved dog, Lexie.

Friday is garbage day. The cans were empty and sitting outside the gate. Normally, I bring both our cans and Mary’s cans in for both of us on Friday afternoon, but my friends didn’t know to do that, so Mary’s cans were still out on the street Saturday mid-morning. When Peter and Christy returned from getting coffee, they diligently checked the gate to make sure it was latched. Then, they carefully came in the front door, making sure to keep Beans well inside. Of course, they then let both dogs out the back door to go to the bathroom. Chewie went straight out to the grass, peed and came right back. Beans carefully inspected where Chewie peed to make sure he peed in the exact same spot and then disappeared around the corner to check out Mary’s glass door in case the cat was sunning herself and then went to the top of the stairs by the gate to take up his gargoyle post. Something in Peter’s gut told him to walk around the corner and just check the gate again, even though he had just checked in right before they came in the front door. When he rounded the corner, his eyes took in two terrifying facts: the gate was not just unlatched, it was open and Beans was making his way up the stairs. As he ran to get him, Beans picked up his pace and scurried past Mary who had opened the gate to put her garbage cans in and then walked a few steps away to talk with a friend who was out for a walk. She saw Beans scamper by, Peter frantically burst through the gate and rush to the front door where he slammed it open and yelled to Christy, “I need you, fast!” before he took off in pursuit of Beans who was running down the walking/ running/ biking trail that is just beyond the road in front of our house.

Distracted by the smells of so many dogs who had been along that trail that day and all the days prior, Beans was torn. Do I run, do I smell, do I pee in all these spots. First he ran. Then he peed until Peter was close. But Peter was a rookie Beans hunter and he thought he had him. He didn’t know about the downward dog, lean left, juke right, could go either direction move Beans had perfected. So Beans evaded him, time and again. With Mary and her friend coming up behind Beans, Peter could run ahead to block his other escape route. Christy was just about in position to prevent him from getting around him on the road, but he saw his window closing and tucked his butt in his most agile and quickest move of all and got past her to take off in Mary’s direction for another twenty yard sprint. But he was breathing in snorts and gasps and needed a break, if only for a few seconds, which allowed Peter to make his way down the trail and get behind him. Now Mary and her friend were in front of him, Christy had the road blocked and Peter had his flank. With the circle intact, they slowly closed as he crouched, snorting and rasping like a dying machine. It did take a final dive to capture him and lug his dense body home. All five were exhausted, Beans from the physical exertion, Mary, her friend, Peter, and Christy from the adrenaline rush of almost losing Beans.

Each day we were gone, I sent Peter a text asking how the dogs were and he replied, just fine, all’s well. I passed the good news on to Beans’ parents and we all enjoyed a wonderful weekend away. When I returned to work on Tuesday, Peter and I were enjoying lunch with a group of friends and I asked him if the dogs gave them any trouble and he then told be the story of chasing Beans. I laughed but understood. It’s one thing to let your own dog out and feel the fear of “what if I lost him?” It’s another thing all together when it’s someone else’s dog.

Later that week, my son stopped by and we were chatting. I asked him how Beans was doing after his weekend with strangers. “He’s perfectly fine,” he said. “You know Beans, he loves everyone. Why, did Peter say something? Did he give them trouble?”

“No, he was his normal friendly self,” I said smiling. “But, he did get out.” The sheer terror on my son’s face for a split second even though the ordeal was over. Beans was home on his own couch with his own blanket as we spoke, and he was still a bit unnerved. I told him the story and he felt bad for Peter and Christy having to go through that.

He also said, “I’m so grateful they got him back. I mean I feel bad Beans did that and obviously it was a complete accident. No one could have seen that coming. But this is why if freaks us out so much to leave him. Unless it’s your dog, you just don’t really know what they’ll do and how to get them back. And, honestly, Peter and Christy did a great job, but no one will work as hard as you will for your own dog. I’m just so glad they could catch him. Beans loose on the trail. God knows how far he could go.”

As he left to go home and probably hug and scold Beans at the same time, neither of which Beans would understand, I thought of the first Bible story I ever heard in my very first Sunday School class. It was 1972, so the teacher had a felt story board and put up a felt fence, felt sheep, one felt sheep way outside the fence, a felt man with a bathrobe (or so I thought), and explained how the felt man who I learned was Jesus would leave all the sheep safe in the fence to go find the one who was lost. Everything my son said rang true. When they’re yours, you know what they’ll do and you know how to get them back. And no one will care as much as you do or work as hard as you will because they’re yours. If you look at the cross, you know that’s true.

Hide and Seek with Mt. Rainier

“This mountain’s presence is much like my love and plans for you. Sometimes it is clear and hangs prominently in front of you, reflecting the light from every direction. Other times, it is shrouded, sometimes for weeks at a time. But it is still there just the same, even when you cannot see it.” It is this that compels me to look each day for Mt. Rainier, whether it be a pristine blue skied day, or an ominous dark clouded storm for the 23rd day in a row. It doesn’t change the reality of what is there.

I’m quite certain part of the point of Wordle is to solve it as quickly as possible. Normally, I don’t play that way. I like to come up with as many words as possible with the green letters I have. Except one day, I was mid-game while waiting for a flight to take off and it was getting to be crunch time and I was struggling to come up with what the word was. I had a G and U in gold, no green letters, absolutely no idea what direction to go, and the flight attendants were starting the safety briefing. Obviously I needed to crowd source so I turned to the young man beside me and asked, “do you play Wordle?” He smiled and said,

“I love Wordle, let me see what you have.” As I handed him my phone, he went on to say with a warm smile, “I grew up in Nairobi and all I did all summer long was play soccer until I was exhausted and take a break to play scrabble, so you asked the right person for help.” I suggested GUANT, turning the G and U to green while asking him if Seattle was his home now or if he was just visiting. He said, “I moved to Washington D. C. for college and because I studied computer science, I came to Seattle each summer to do internships at different tech companies each year. I fell in love with the Pacific Northwest and moved here to work for Microsoft in October, 2019,” and his face told me he felt betrayed by the Pacific Northwest.

“Aw, that’s tough. If you had only ever been here in the summer, you probably thought it was always blue skies and mountains every day, huh?”

“Exactly,” he lamented as we finished my Wordle with GUARD in all green just as the flight attendants shut the door and it was time to put my phone in airplane mode.

He continued, “not only did the beautiful mountains hide for months and months and it rain and rain and rain, but then the pandemic kept me from my scrabble group.”

“Where did you find a scrabble group?” I asked.

“Just Meet Ups. I looked for a scrabble group on Meet Ups and showed up to a group of sweet 70 year old women who handed me my ass with a smile on their face, offered me a cookie and then handed me it again. It was very humbling. As if I needed another reason to be depressed.”

The Blue Angels with a Mt. Rainier backdrop - a Seafair specialty.

I went on to ask him all kinds of questions about Nairobi, moving to D.C., and moving to Seattle. He kept coming back to the mountains here and how much he loves seeing them and how much he misses them during the winter months, especially Mt. Rainier. I have had this same conversation with so many people who move to Seattle from places without mountains or with mountains that they miss. The thing about the mountains in Seattle, if you’ve never been on a clear day, is that they surround us: the Olympic range is to the west, the Cascade mountains are to the east, Mt. Rainier is a pillar of stunning beauty standing on her own in the south, and Mt. Baker reflects her in the north. And Seattle is hilly, so on a clear day from the top of most any crest, they steal your breath in every direction like a cold plunge.

One day a friend of mine was worrying for me that my oldest daughter, who likes to move to continents far, far away from me, might never come back. It happened to be a pristine summer day and we were on a boat in the middle of Lake Washington with my daughter getting ready to surf in full view of Mt. Rainier, and I said with a wry but confident smile, “I know she’ll always come back home because she loves this lake and that mountain.” She winked and agreed.

Almost six years ago, we moved to a house where, from the very tip of the corner of the back yard, on a clear day, you can see Mt. Rainier. Conversely, on a cloudy day, I can stand there and see where Mt. Rainier is, even when I can’t see her. Even though I can see the clouds from my kitchen window, I still go outside and to the corner of the yard to look because maybe, just maybe, I might still get a glimpse of her. Moving to this house also created a new route to work that includes driving across the longest floating bridge in the U.S. that spans Lake Washington to get from Seattle to the east side. From the middle of this bridge, for just a minute at 60 miles an hour, there is a clear view of Mt.Rainier, on the days she’s out. Other days, there is a clear view of where she stands behind the clouds. Sometimes only her top is poking out. There are rare days when a thin ring wraps her middle. On my way home each night, I have to look back over my left shoulder to glimpse her, which could be dangerous, but the traffic that time of day is quite slow, so it’s usually ok, and I can see how she looks in the evening light – on lucky days. The sun sets over behind the Olympics, casting a soft pink glow on her ever white top, a trait we share. As you are beginning to see, I spend a lot of time looking for and at this beautiful mountain. Imagine how taken I was with the picture my daughter, Carly, sent me of her view from near the top of Mt. Rainier – above the clouds at sunrise - on her climb last summer.

Mt. Rainier at sunrise - close to the summit.

One day, as I rode my bike across the bridge to work, much slower than 60 miles per hour, the sun was just rising up to the east of her, casting a soft orange glow on her south east side, I thanked God for her beauty and a thought came to my mind that I could never have come to on my own. “This mountain’s presence is much like my love and plans for you. Sometimes it is clear and hangs prominently in front of you, reflecting the light from every direction. Other times, it is shrouded, sometimes for weeks at a time. But it is still there just the same, even when you cannot see it.” It is this that compels me to look each day for Mt. Rainier, whether it be a pristine blue skied day, or an ominous dark clouded storm for the 23rd day in a row. It doesn’t change the reality of what is there. This is what I shared with my Wordle friend on the plane who was accustomed to the blue skies of Nairobi and his ever-present view of Mt. Kenya.

The view of where Mt. Rainier is behind the clouds.

after the bad thing happens

A bad thing happened to it and it needed to rest, some tender specialized care, and a chance to get its bearings about it. But once those little roots started, they grew quickly. While it took two months for the little guy to start the nubs of new life, once they started, they took off like a puppy growing into its paws. Each time I checked on them, they added clear growth. Before I knew it, they had three inches of roots coming out of the breakage point and were ready to be planted in rich soil in their own beautiful new pot. So, I gave it to a friend at work and now he has a new plant instead of just a bad thing happening to my plant.

I have always loved getting my hands in the dirt outside. But since moving to the house we live in now five years ago, I’ve had pretty good luck with house plants too. It started with a house warming gift, then my daughter and I discovered a fabulous nursery in north Seattle, Swansons; they have the most gorgeous house plants. I brought two home. Then we went back and I brought one more home. Now I have eleven. We live close to water, so I think the moisture in the air is helping them thrive. Every few weeks I take the large ZZ plants outside to water so I can really drench them and let them drain for a few hours before I bring them back in. They have become huge (by my standards and ability to grow house plants), sprawling, and absolutely fantastic. I love them. My grand dog Beans (he’s a French Bulldog) loves to hide behind them.

On one of these trips through the front door, which is a bit of a Cheeze Whiz experience for the plant, one of the stems broke off. Rather than toss the broken stem into the compost, I put it in a vase of water and kept it on my kitchen counter where it gets indirect bright morning light. I kept the water clean and gave it some time. After a few months, I noticed tiny white nubs of root growing from the breakage point. It wasn’t quite ready for soil and a pot yet. A bad thing happened to it and it needed to rest, some tender specialized care, and a chance to get its bearings about it. But once those little roots started, they grew quickly. While it took two months for the little guy to start the nubs of new life, once they started, they took off like a puppy growing into its paws. Each time I checked on them, they added clear growth. Before I knew it, they had three inches of roots coming out of the breakage point and were ready to be planted in rich soil in their own beautiful new pot. So, I gave it to a friend at work and now he has a new plant instead of just a bad thing happening to my plant.

One afternoon I was at a reception for a well-respected colleague who was leaving his position when a co-worker, who used to be a student of mine, came up to introduce me to a person new to our staff. In the introduction, he told her how much I helped him when he was my student and went through a difficult time. He was a very bright student who had a full ride college scholarship for his academic promise. But he struggled mightily and faltered several times. We spent many hours in my office as he tried to get his bearings. He took some time off from school to take care of himself for a while, came back as an online student for a bit because it was easier for him to manage, and finally returned to complete his degree. Instantly, the broken plant came to my mind. I told him about this plant that had a bad thing happen to it. And when that bad thing happened to it what it needed was a little time to rest, some care and a chance to heal, and now new roots are growing and it’s ready to thrive again. Emotion clouded his eyes and he thanked me. I told him I think God’s creation is very consistent and we are a part of it. A bad thing can happen to a plant or a person and with time and loving care, both can find a way to thrive again. Like the new plant, this former student who struggled through his pain and regained a new place from which to thrive is now a graduate enrollment counselor who helps people find their path.

Education - getting your money’s worth

Are you someone who hates wasting? I am. We eat leftovers. I’m constantly turning off lights, adding water to the bottom of the soap, milk to the last of the salad dressing, you get the idea. I love a good deal and really have to restrain myself when there’s a good BOGO because I can be tempted even when I don’t need it – just because it’s a good deal – which makes it not a good deal. I always want to get my money’s worth.

One of the most ironic things about my life is I grew up to be a teacher and go to school my whole life, specifically, an English teacher. The first thing that makes this ironic is I used to quit school all the time. Growing up, my family lived across the street from the elementary school I attended and so whenever school wasn’t going particularly well for me on any given day, I quit and went home. For years, if another student commented on my mis-matched clothes (I liked to get creative and mix it up, and swap out what my mom laid out for me after she left for work), my extremely hairy legs, or I just didn’t really feel like going back to class after recess, I’d just hide in the huge drainage pipe on the playground when everyone else went inside and then sneak across the street to hang out with my dog and read books in my room. Never one time did anyone mention the fact that I wasn’t there for the afternoon. Of course, I had to pay attention to which shift my stepdad was working because I could only do this when he was working days. He was home when he was working swing-shift and sleeping on the graveyard shift. Then, when I was in seventh grade, my sixth-grade teacher had recommended me for the language arts challenge program in junior high. The challenge teacher didn’t agree that I belonged and made my mom take time off work to come to a conference where she told both of us, “she is not gifted or talented and doesn’t belong in this challenge program. She’s an over-achiever and knows how to work hard but doesn’t belong here. I can’t kick her out, but I recommend she move down.” It didn’t fill me with academic confidence and the junior high was too far from home to quit, so I decided to stay to prove her wrong. Finally, the last ironic thing about me going to school every day for my life is the fact that I chose to be an English teacher. My English teacher for my sophomore year was perhaps one of my least favorite teachers of all time, even worse than the seventh grade challenge lady. She was prissy, way over dressed for the occasion of teaching high school and mailed it in with the lesson plan of having us write thought slips for her to read aloud every Friday. But, after 15 years teaching high school and college English, I now work as an academic advisor at a small liberal arts university, and I love it. Partly because despite the ironies of quitting school several times a week for the first several years, being told I don’t belong, and not having English teachers I connected with, I love school, learning, and everything that goes with it. As a student and even more so as a teacher, I am dumbfounded when students don’t go to class, don’t do the reading, don’t do the work, and otherwise take a pass on the opportunity to learn.

My colleagues and I discuss this phenomenon all the time. We read the educational research that tries to understand how and why some students thrive and others don’t, what students need to be ready to learn, what fills or is missing from their invisible backpacks that enables or makes it difficult for them to navigate the complicated educational systems – particularly at the higher-ed level, what kinds of social and systemic issues are impacting their ability to succeed, what familial supports they need, what kinds of emotional and mental health concerns are preventing them from being fully present and able to engage in learning – the list is very long. Of course, not every potential support or detriment is present for every student. In one of these conversations, one of my colleagues said she was talking with her husband about a student who was not showing up and he said, “education is one of the few things where we don’t try to get our money’s worth.”

And yet with all of the considerations listed above that make engaging in learning difficult, his statement really struck a chord in me, I think because I am always trying to get my money’s worth, and I so love learning. I work at a private college where tuition is rather steep. Students and their parents are paying close to $36,000 a year for a college education. Many are taking out considerable loans. What made his statement ring so true is I frequently hear students tell me the reason they are falling behind in their classes is because they don’t go, they don’t do the reading, they don’t do the work, or they didn’t study because they were distracted by friends, phones, games, or they just aren’t motivated to do the work. This one really gets me. They talk about wanting to find their motivation like it’s on a shelf at Bartell’s down the street. When I hear a student tell me they chose to take a nap rather than go to class, my mind quickly figures out the cost of that nap in tuition wasted. But more than the tuition wasted, I am always struck by the missed opportunity to learn, to become better at thinking, better at solving problems, better able to understand themselves, others, and the world they are moving into.

To make this point, at the last orientation for new students I conducted, I had one of my colleagues sit in the front of the auditorium while I was presenting. He had a full meal from Chick-Fil-A. I asked him to make a production of laying it all out. The fries smelled delicious. He opened the chicken sandwich and carefully spread the special sauce all over the bun. He opened another package of sauce and dipped his first waffle fry and ate it. Then he thumped the straw on the table to push the paper down enough to be able to pull it from the wrapper before putting it in the dark, sugary drink. He slurped some up and set it back down before taking his first bite of the warm, tender chicken. He ate three bites of the sandwich, two more fries, and then carefully wrapped it all back up and threw it away. Of course, the students were paying absolutely no attention to what I was saying. I mean, they were trying, but they were so distracted by his eating. That is until he threw most of it away. Then they weren’t even trying to pay attention to me at all. One of them interrupted to ask, “why did he just throw that away?”

“Ah, I’m so glad you asked!” I answered. I turned to him and asked, “Robert, why on earth would you go to all the trouble of driving to Chick-fil-A, paying good money for a meal, carefully preparing to eat it, take only a few bites, and then throw it away?”

To which he said, “I dunno.”

That really got them. I asked, “does anyone know what I was talking about when Robert threw his food away?”

One student had the gist, “something about going to class.”

“Yes, exactly. The importance of going to class. As you may have guessed, Robert is not just eating and throwing away Chick-fil-A in front of you while I’m talking for no reason. What are your thoughts about what you just saw?”

The students were catching on. They were horrified by the waste of something so valuable to them as a Chick-fil-A meal. Then I made sure to make clear that college is not for everyone and not required for a meaningful life, but if you’re going to enroll in college and pay for what you, your parents, or the loans you’re taking and will have to pay back whether you get a degree or not hope will lead to meaningful work that will support your life, then taking a nap instead of going to class, not doing the reading, not doing the work, trading Netflix or TikTok or your video game of choice or fear of failure rather than asking for help is like throwing away that meal you just paid for. If you are going to pay for it, please, for God’s sake, get your money’s worth. I understand the challenges and barriers that make learning and showing up very difficult, and we have all kinds of resources to help with those: nearly free counseling, academic life coaching, free tutoring, free research assistants, etc. I want them to show up to learn not just the specific content of each class, but learn how to think, how to communicate, how to solve problems. These are the skills that transcend subject matter and will nourish their lives; they have mine.

Pruning

February is a tough month for folks who live in Seattle. I’m sure it’s worse for people who live in far colder and far darker places such as Anchorage or Minneapolis or Bangor. But, for Seattleites, it’s been gray and wet for months on end and blue sky that contrasts the stunning Cascade and Olympic Mountain ranges anchored by Mount Rainier and Mount Baker is a distant memory. But what really makes it tough is that we know it is likely to be the end of May before we get a reprieve from the rain and spring really arrives, or in a bad year, maybe even deep into June. For me, however, there is a bright spot when February rolls around. It’s time to bundle up and get outside to start cleaning up the last of the leaves from fall and prune my roses and trees. I have always loved getting my hands in the dirt, mostly because through his creation is the clearest way I understand God. All throughout the spring, summer, and fall, I am constantly outside on my knees, hands in the dirt, regularly thinking about some aspect of God’s character, ways, love, or truths. Winter makes this hard and so when pruning in February comes around, it’s oxygen after holding my breath underwater for too long.

Never do I prune my roses, in February and all throughout the growing season, that I don’t remind myself of John 15 and think of all the ways it seems like pruning the rose bush is harsh and brutal but when done right, promotes health and growth and the opportunity for beauty and continual new blossoms, not just the first buds on last year’s tired branches and that’s it for the season. “I am the true vine, and my Father is the gardener. He cuts off every branch in me that bears no fruit, while every branch that does bear fruit he prunes so that it will be even more fruitful.”

For as much as I’ve tried to learn about roses: classes I’ve taken, articles I’ve read, YouTube videos I’ve watched (every season before I start), people I ask, I still feel a little bit terrified inside when I cut so much off. So many beautiful buds. With very sharp clippers.

While I love my roses and think I have a good bunch of bushes in my yard with my 11, it seems every time I bring it up, the person to whom I’m talking has 30 or 40 bushes and knows far more than I. So, I’ve learned to ask questions. Pruning for the season’s bloom starts at the end of the last season. Just as fall makes up its mind to get serious and start frosting the grass white and the leaves deepen red and amber, it’s time to strip the branches. Take off all the leaves so the wind has less to catch throughout the winter and snow has less to build up on and weigh down and damage the plant. Then, it’s good to prune in February, just as they’re starting to bud for the new season. This will allow you to see where the plant is sending shoots in crazy directions and set it on a healthy path. Cut all the shoots crossing into the middle of the tree or rose bush so they are growing in the direction of the bud.

You want to make sure you have sharp clippers to make a clean cut. First, remove all blooms and leaves from last season that may still remain or that managed to bloom after the fall trimming to prevent disease. Next, cut off all the dead woody branches left from last year. This will allow for new growth. What supported big, beautiful blooms last year will hold the plant back from the same this year.

And, then I fertilize them. Around the base I sprinkle the nutrients they need to grow strong robust blossoms and develop the defenses they need to fend off aphids, and mildew and black spot that threaten their vitality and beauty. This is a constant vigilance I maintain. At least once a week, I am watching, trimming, checking – to make sure the faded and the dead blooms are removed to make way for the new and the whole plant is fed and protected. From February all the way through to the last days of fall. And I’m just an amateur gardener. Imagine the care the master takes.

Scars

Can these scars ever be cool? Perhaps language is failing here. Cool. Emblems of resilience. Signposts of pain. Heralds of healing. Storytellers. Historians.

Two of the many things I love are dogs and running. One February morning, early enough to bite at my cheeks and nose, but late enough that the sky was just beginning to blush, I was out for my morning run. It was a Saturday, so traffic was quiet, and the morning mist was hovering over lawns wet from the night’s dew.

When I’m running, I can get really lost in my thoughts and lose all awareness of my surroundings, so I didn’t notice the three dogs come out from the open gate until they were in the air, jaws open, just inches from my face. I managed to get my arm up in time to protect my face, but two of them sunk their teeth deep into the flesh of my arm, one just above my elbow and one just below. The third couldn’t get around the first two to reach me. They were pit bulls, I came to realize as they shook my arm and the third tried again to leap over the two that had me in their jaws. My only thought was, “I can’t kick them or they could knock me down.” To be honest, I’m not sure how long they shook my arm before I looked back and they were all three running, ears back and tails down, back to the open gate they came from. It didn’t take long for me to think, if you’re running away, so am I, and I ran about 10 yards before I started to feel dizzy and nocuous and noticed the blood seeping through my shirt and running out of my sleeve. I stopped and sat down with my head between my knees so I wouldn’t pass out. A car stopped beside me and a woman who was passing by in the opposite direction who saw the attack, called 911, and came back to help me had her arm around my shaking shoulders. After she got me in the warm passenger seat of her car, she asked me, “how did you get them to let go and leave you alone? They had you.”

I looked up and said, “I don’t know. I think an angel must have showed up.”

She got a very concerned look on her face, patted my shoulder, and said, “I think you’re just upset.” She waited several feet away from me until the police and aid car arrived.

For days, I couldn’t run outside. For weeks, I had nightmares of dogs coming at me and I’d wake up terrified. So, I started memorizing the book of Colossians as I went to sleep and filled my mind with something other than the memory of that terrifying experience. My husband ran with me when I first ventured to run outside again. And, slowly, my fear healed and faded to match the faint scars of their teeth marks on my arm that my kids assure me are cool. Now, years later, frequently when I wear short sleeves, someone will ask me, “what bit you?”

There was a 9.2 earthquake off the coast of Alaska in 1964. The damage to Anchorage and the surrounding cities was devastating. The tsunami that followed is the largest ever recorded reaching 1,720 feet (taller than the Empire State Building) when it struck the tall banks of Lituya Bay. While the cities are fully rebuilt, 80 years later, you can see the scars left on the landscape from the tsunami.

My grandparents grew up during the depression. They always, always, always cleaned their plates. And when you were at their house, so did you. Food was precious to them. My grandpa made logs for the fire out of newspapers wrapped in wire and fished the wire out of the fire and re-used them until they were so brittle, they broke. My grandma canned hundreds of jars of beans, peaches, pears, apple jelly, jam, pickles, beets, onions, carrots, and everything else that grew in their garden every year. She could tell you with pin-point accuracy how many jars of each she had at any given time and from what year they came. You couldn’t see those scars, but they never left them. My sister, brother and I used to spend weeks at a time at their house each summer helping pick the fruits and vegetables and can them. We loved the rows and rows of jars filled with green beans and apple pie filling on shelves in our garage all year long. We understood why we always had to clean our plates at Grandma and Grandpa Rhodes’ house. We didn’t necessarily see them as scars, but they were cool to us. Maybe not the homemade clothes, but the rest, that was cool.

My brother’s ears are ridiculous. He has been wrestling since he was 10 years old. I’m not even sure what the medical term is, but wrestlers call it cauliflower ear. After years of grinding your ear against the mat, day after day, they become so disfigured, they don’t even look like ears. He cannot use headphones unless they’re the huge over the whole ear kind, and even those don’t really fit quite right. Forget about a Q-tip. It’s caused by fluid filling the entire ear, every fold and canal after the insult of being ground against the mat. The headgear doesn’t help prevent this. Over time, this fluid hardens to feel just like cartilage, kind of like the bridge of your nose. In fact, his are so notorious, they earned him a spot in a pre-Olympics Nike commercial once upon a time that featured many Olympians and their scars, battle wounds, earned from years in their respective sports. Now that he’s retired from both wrestling and ultimate fighting, he could have them repaired and restored to look like ears again, but he wouldn’t dream of it. He loves them for he’s earned them, and they are his battle wounds, hard earned and hard fought.

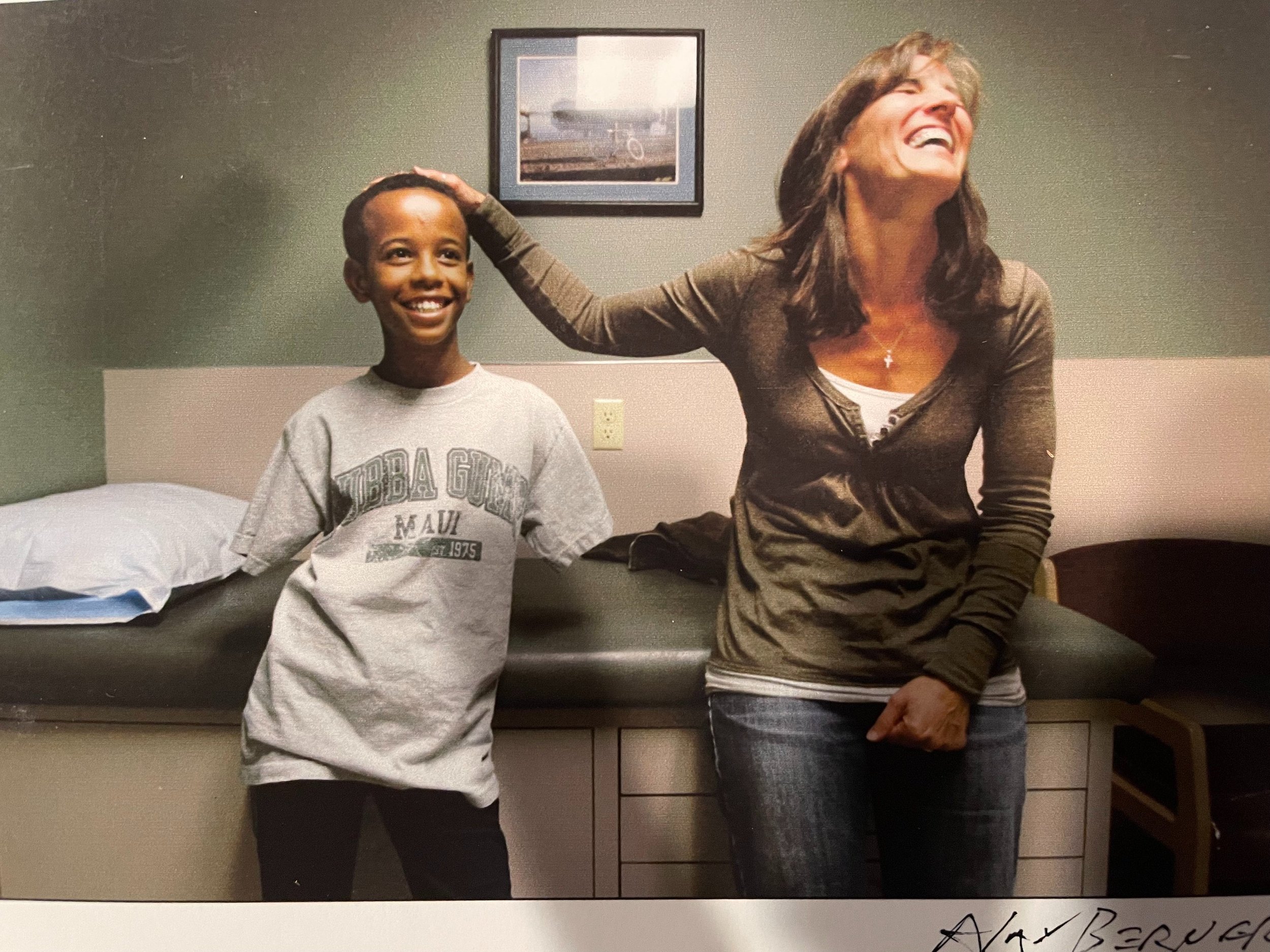

There was a time when a young boy from Ethiopia lived with our family for a few months. He came to the US for medical treatment. He’d lost both of his arms in an act of unspeakable violence. One arm was too damaged for a prosthetic limb, the other barely long enough. But oh, how he loved to swim. While it was not me walking from the locker room to the crowded pool deck with bare stubs for arms while children and parents alike stared after him, I felt his discomfort. There was no language barrier for this pain. My family and I helped him eat, brush his teeth, dress, bathe, scratch the back of his head, and buckle his seat belt, to name a few things he needed help with. These are independences toddlers fight for and demand from their parents. He was 14. It was a terrific battle between helping him and helping him learn to do these things for himself, especially after he got his “arm.” It was a triumph to watch him ride his custom-made bike. It was a triumph and a heartbreak to see him go back home to Ethiopia with one prosthetic arm and as many supplies to support its use as possible. Can these scars ever be cool? Perhaps language is failing here. Cool. Emblems of resilience. Signposts of pain. Heralds of healing. Storytellers. Historians.

As the COVID-19 pandemic transitions to an endemic, the speculation of what the scars will be are emerging and taking shape. On the young children whose first social interactions with the public have been distanced and through masks, on school-aged children whose first school experiences have been disrupted and online, on middle-aged children who didn’t develop social skills with their peers, on middle and high school aged children who didn’t go through the process of connecting more with adults outside their families and with their peers than with their parents and siblings – if they were fortunate enough to have them, on adults who were confined to their homes and small or non-existent social circles for such an extended period of time, on society as a whole after witnessing so much death and protracted uncertainty, on the nurses and doctors who cared for the dying day by day and month by month as not only medical providers but surrogate family members for last breaths, on the local and global economy, on international relationships, the list could go on and on. What will the scars look like and how will the wounds heal to be scars? How will today’s children describe their grandparents who grew up during the pandemic like I’ve described my grandparents who grew up during the depression?

Will these scars be cool? A scar can be a sign of pain and trauma or an emblem of resilience and healing. Too often all we see are the scars or end result, and don’t understand what happened between the injury and the resulting scar. Dr. Brene Brown in Rising Strong calls this gold-plated grit where we gloss over the messy second act and skip right to the end where the moral, gem, lesson lies. No one wants to talk about the nights after the dog attack I bolted up out of sleep terrified from a nightmare of dogs coming at me. No one wants to hear about the mornings I stood paralyzed by my front door with my running shoes on unable to step outside. No one wants to talk about the time my husband got a little too far ahead of me on those first mornings running back outside and I panicked and stopped, unable to even take a step. Or about the time, months later when I was walking with my daughters and a huge dog inside a car barked and lunged at the windows at us. Before I knew what was happening, I was flat on my face on the ground shaking. It took both of them to get me back up and away from the barking dog. Mine was a terrifying, but quick experience. My scars are visible but coverable and manageable. I don’t mean to minimize what a life-threatening or excruciatingly painful experience may have been like, one that may have left life altering scars – visible or not. Scars can be cool, if they heal to an emblem of resilience. But don’t gold plate that process. It’s not easy. And not all scars are easy to bear. But what I’ve learned from those with scars from trauma far worse than any of mine, they can heal.

Compost

The lists are easy. The process is clear. The practice will require more courage and determination than you think you have, but it’s just that, a practice. Begin each day and don’t ever stop no matter what happens. The process must be continual, and you must believe it’s well worth the effort. Because “how hard can it be,” is always a dangerous question - whether you’re growing vegetables, baking bread, or cultivating a heart that is open to God and ready to sustain a thriving life.

The first year of the pandemic gave people lots of time at home. Some took up baking bread, or at least they squirreled away all the flour and yeast in the known world to do so. And the learning curve must have been tough on their digestive systems because they also needed all the toilet paper available to humanity as well. No judgement - I understand what can happen when a recipe goes south. I was among the “I think I’ll grow my own vegetables, how hard can it be,” crowd. Turns out, like everything, there’s a lot to it, starting with the dirt. Excuse me, soil. Rookie mistake.

April 2020, I headed into my backyard and put some lettuce seeds in the raised planter boxes the previous owners of our home built. The two 6’ by 2’ rectangle boxes had been staring blankly at me like the hollowed-out eyes of a jack-o-lantern in early November for the whole of the previous summer. I eagerly bought seed packets for green leaf lettuce, red leaf lettuce, and romaine, but no kale. Those seeds were as valuable as toilet paper, apparently. And four zucchini plants. It only took about twenty minutes to make the straight-ish rows about 1/8” deep, sprinkle the pin sized seeds, cover them over, toss the packets into the recycling, diligently water, and wait. It was a pretty nice spring in Seattle back in 2020, weather wise at least, so my little lettuce plants started to peek through the soil pretty quick. You’d think I was in The Martian and these were the potatoes that were going to save my life. While everyone else was watching The Tiger King, I was watching my lettuce. My neighbor, who knows how to grow vegetables and had been doing so for years, came over to stand 6 feet away and offer her expert observations. “What kind of lettuce is this row?” she asked.

“Oh, I can’t recall. I have 3 different kinds in here but I don’t remember which is which.” It then occurred to me I should have saved those little packets. An instant memory of my grandparents’ garden with little stakes with the seed packets standing sentry at the end of every row warmed my heart. “Genius,” I thought.

“When did you plant each row?” she asked again.

“I planted them around the middle of April,” I said proudly.

“All of them?” she gently asked with a sense of either puzzlement or pity, I couldn’t tell which.

“Yep, all of them,” I said, still proud. Again, it dawned on me. “Oh, that wasn’t such a good idea, was it?”

“Well,” she started compassionately. “If you stagger them, you won’t have all of your lettuce to eat all at once.” We stood in silence for a moment. I could tell she was beginning to wonder if she should ask anymore questions. Finally, she ventured again, tentatively. “What complimentary crops did you plant?”

At that, I just laughed. “Oh, I didn’t plant any complimentary crops. Just lettuce and these 4 zucchinis.”

Now she was laughing with me. “Do you know how big zucchini plants get?”

“Nope.”

“Huge. And each one will give you tons of zucchini.”

“Great! I’m the only one who likes zucchini.” We were laughing so hard we both bent over. I managed to choke out, “I’ll bring you some.”

She finally caught her breath and said, “what about your soil? How did you prepare the soil and what are you doing about bugs?”

“Absolutely nothing,” I laughed.

“Well, it’s not too late for some good organic bug deterrents, but next year, you’re going to have to work on your soil before winter.”

And so it began. I started learning how to prepare soil, stagger my planting such that the harvest isn’t all ready at once, and I have learned about the three sisters: corn, squash, and beans. And while I’m still a rookie vegetable gardener, I’m not new to gardening. I love having my hands in the dirt, working in my yard, keeping my beds weeded, grass trimmed and mowed, roses blooming, bushes neat, and pots brimming with color. But I’ve never given much thought to the soil before, at least not beyond what color I would prefer my hydrangeas to be. But as I’m learning how to cultivate rich soil, a whole new world is beckoning. It feels like the first time I suctioned a mask to my face and peered at the complex world under the ocean waves – that kind of mask, not a KN95, but fair assumption. We are talking about spring 2020 after all.

On the one hand, building nutritious soils is fairly straightforward. You need good minerals that come from a natural composting process with some greens and some browns so plants can grow and thrive. But, as much as it might seem like this is about gardening, composting, and soils - it’s not. To be honest, I don’t know near enough about that to say any more than I have. Just after attending the Seattle Flower and Garden Show with my daughters last February and listening to a gentleman present on native plants and what they need, my pastor was talking about The Parable of the Sower, and I was struck by the similarities between what he had said and she had to say. While he was talking about plants that are native to the Pacific Northwest and the different kinds of soils they need to thrive, she was talking about the different “soils” or condition of a heart necessary to receive from God. My mind wandered to think about what the composting process of one’s life is in order to maintain a heart where God is welcome, and life thrives.

In the parable, some seeds fell on the hard-packed soil of the walking path. No chance of growth there. Good soil needs to be tilled, turned, loosened all the time. This is such an important process because the normal course of seasons hardens soil, much like our hearts. The cumulative effect of daily fears, failures, offenses, injustices, even successes have to be tilled in a composting process and then rototilled into the soil of our hearts. Compost has to be churned with love and infused with the oxygen of examination and the warmth of truth in order to break down the natural elements of a life and feed the soil of a heart in order to foster growth. If you shove down and trample your fears and triumphs, your failures and friendships, your offenses and offenders, those you’ve angered and who’ve angered you every day - your heart will be as hard and as uneven as a well-trodden path. You may think you’ve tamed it, whichever of the pieces of your life you’re tamping down but, in fact, they will have tethered you. For me, a great example of this is withdrawing out of fear from my husband in conflict. Having lost all contact with my dad when I was five with no explanation until I was nineteen and then growing up with two abusive, alcoholic step-dads, I hide at the first sign of conflict in fear of abandonment. I am the most ardent of rule followers, so when the rules said, everyone wear a mask, a mask I wore. He is less of a rule follower and far more independent minded than I. Many people took issue with the masks for many reasons; for him, he was more than willing to wear a mask for his own safety and for others’ safety. But he bristles at being told what to do, so there was a tension there and he drew some lines about wearing his mask in his office all day, every day. But he shares his office with others he decided to make a part of “his bubble.” However, that made them a part of my bubble, and I wasn’t comfortable with that. As you can imagine, for both of us, this conflict had little to do with the masks and more to do with my fear of rejection and abandonment that I try to abate by making sure I’m doing everything right all the time, which is impossible and exhausting. And when I sense rejection is near, fear mounts inside my gut like I’m a little kid being chased, and I withdraw. For him, it was about his vow of independence he made to himself when he was very young and his parents divorced. When anything infringes on his ability to control himself and his environment to prevent that kind of pain again, he shuts down. It’s a perfect storm. Thirty-five years of marriage have unfurled this scenario between us like flag billowing in a breeze. Understanding helps, but man, softening the soil on those hard-packed responses is back-breaking work.

You also need plenty of soil. If it’s shallow, seeds may grow at first, but they will not thrive. Without deep soil, the plant cannot develop roots that will sustain life. The soil holds the water and the minerals, but it also provides stability. A heart that is unavailable, hidden behind the rocks of past accomplishments, hurts, or anger over hardships is shallow soil. Relationships and opportunities to grow and live into your gifts in effective ways will be scorched by seasons of drought where the flow of new water and nutrients lags and your roots don’t have deep soil from which to draw. Shallow roots can also leave you vulnerable to topple when abundance comes because you will not be grounded well enough to handle the money, notoriety, attention, or responsibility it brings. Both the absolute bounty and the beautiful as well as the abominations of life have to be tossed into the compost pile of the heart and churned together. Be grateful for your blessings, forgive yourself and others their mistakes, learn and grow from failure, be generous with your bounty, be humble regarding your gifts, and take full responsibility for your shortcomings.

Even plants that initially thrive in deep, rich soil face threats. A heart that is open to love, examination, and truth is also prey to worry and distraction. These can choke and crowd the best of plants. Regular weeding is important, particularly in good soil because everything grows in rich soil. Make sure you have honest relationships with courageous people who will keep you growing in self-awareness for there are fewer gifts of greater worth.

So what makes for good soil? Compost replenishes the nutrients that time and the planting process drains from the soil. Compost is made up of the healthy stuff in your life that you no longer need or can use, or that was once good and beautiful but is now rotten or beyond its useful life. Not everything makes for good compost, just like not everything is good for a human life or body. Animal fats and greasy foods promote fungus growth in your literal vascular system and in your compost pile, and as it turns out, metaphorically in the soil of your heart too. Harboring resentments and malice for another person, no matter how guilty they are, will only bring rot to your very soul. Shackling yourself with shame has the same effect. Dr. Brene Brown writes in Rising Strong about ways to rise strong from what she calls “face-down moments” in life when you’ve failed. Process the story you’re telling yourself and reconcile it with the truth. Take stock of what you’re feeling in your emotions and in your body. Own your part, learn, grow, and move forward.

For good compost, you need some green and some brown. Good green compost adds nitrogen and comes from things such as the parts of fruits and vegetables you don’t eat or that have gone bad, coffee grounds, eggshells, or stale bread. Brown compost is rich in carbon and comes from things that were also once beautiful or useful but are no longer such as fallen leaves, faded blossoms, black and white newspaper, wine corks, used paper napkins or paper towels as long as they’re not greasy, or shredded clean cardboard. Any or all of these could be added to your compost pile and - when turned regularly to be kept warm and exposed to oxygen - will break down and become a rich, nutritious sustenance to keep out weeds and promote growth. Or, you could take what was once useful and beautiful or is beyond its life and now rotting and shove it in a big black plastic bag, seal it tight and send it to a landfill where it will produce toxic methane gas. Same raw material, vastly different outcomes. The same is true of the elements of your life and for your heart.

Of course, this sounds over-simplified for the soil in your garden boxes waiting for this year’s crop or your heart wanting for God or a sense of living from a place of abundance; it’s not easy to nurture balance and health. The lists are easy. The process is clear. The practice will require more courage and determination than you think you have, but it’s just that, a practice. Begin each day and don’t ever stop no matter what happens. The process must be continual, and you must believe it’s well worth the effort. Because “how hard can it be,” is always a dangerous question - whether you’re growing vegetables, baking bread, or cultivating a heart that is open to God and ready to sustain a thriving life.

what makes it into your backpack?